The History of

The Art and Practice of Falconry in Ireland

Falconry has a long and fascinating history in Ireland that possibly dates back to its earliest inhabitants, nearly 10,000 years ago. The remains of goshawks found at human settlements at Mount Sandel, Coleraine (c.7000 BC), Dalkey Island, Dublin (c. 4000BC) and Newgrange in the Boyne Valley (c. 3200BC) leaves us in no doubt that a unique relationship has existed between humans and raptors for a very long time.

Early References and

Royal Connections

The earliest written reference of falconry in Ireland is in the Irish text The Life of St Colman Maic Luachain in the 7th Century, in which Domhnall, the King of Tara is described as having two hunting hawks. Definitive and consistent falconry references only appear in the 12th Century when the arrival of the Anglo Normans finally secured falconry’s place in Ireland, albeit amongst the nobility.

At this time, the country already had a reputation for providing the best hawks available. The legendary High King, Brian Boru, is reputed to have gifted hawks and falcons along with horses and hounds to European royalty as he sought to establish diplomatic relations throughout Europe.

Ireland’s Reputation

for Exceptional Raptors

In 1188, the Welsh monk Giraldus Cambrensis wrote in his book Topographie Hibernae (The History and Topography of Ireland) about the abundant game and raptors: ‘Ireland has none but the best breed of falcons.’ Raptors, particularly Irish goshawks, became a valuable resource to pay rent or to gain political leverage with overlords. A lucrative black market soon developed reaching a point in 1481, where stiff levies had to be imposed on trappers and tradesmen:

‘Whatever merchant shall carry a hawk out of Ireland shall pay for a hawk 13 shillings four pence, for a tiercel six shillings and eight pence, for a falcon ten shillings and the poundage upon the same price.’

Regulations

and Trade

But legislation existed even before this. In 1218, Reginald Talbot was heavily fined for illegally trying to smuggle a goshawk out of the country at Dalkey in Co. Dublin. In 1386, during the reign of Richard II, a proclamation was made at Drogheda against the export of raptors, and rigorous searches took place to curb illegal trade.

A 14th Century document from Kilkenny Castle details the three types of hawks used for rent payment. In 1531, Archbishop Cromer, the Louth-based Bishop of Armagh, presented a pair of hobbies to Henry VIII. In return, Henry committed an annual gift of two goshawks and four wolfhounds to the Duke of Albuquerque in Spain.

Raptors in Legal

and Social Life

In November 1562, Irish chieftain Shane O’Neill sent Queen Elizabeth two horses, two goshawks and two wolfhounds. The Earl of Thomond at Bunratty Castle, Clare, has his signature on legal documents from 1615 in which the rights to his harvest of goshawks are made legally binding.

In 1626, Murrough O’Flaherty of Bunowen directed in his will that his third son, Bryan, be left the townland of Cleggan ‘excepting onlie the aiery of hawks upon Barnanoran’ reserved for his eldest son. Parish records from Co. Down (c. 1600) even noted that bells on hawks were to be removed before entering churches.

17th – 18th Century:

From Nobility to

Popular Practice

Charles II’s viceroy Lord Ormonde established the Phoenix Park as a Royal Hunting Park in Dublin, stocked with deer and pheasants, and enclosed by a high wall. In 1693, the Dublin Intelligence newspaper offered a reward of 30 shillings for the return of a lost hawk belonging to Lord Capell, Lord Deputy of Ireland.

By 1747, Phoenix Park was handed over to the people of Dublin. In 1762, Lord Bandon maintained a mews of hawks and a falconer at Ardfert Abbey in Kerry.

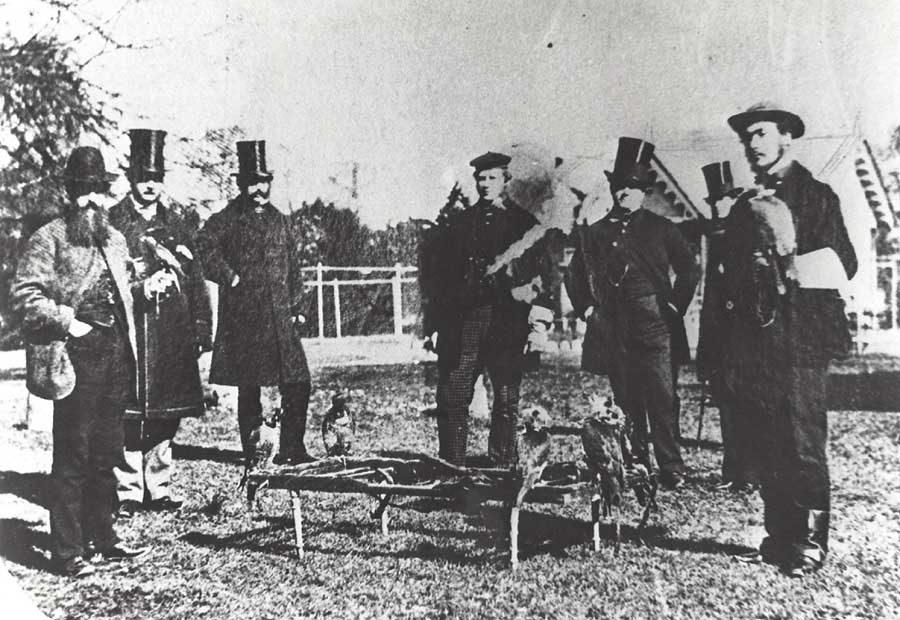

Falconry on the Curragh and the Rise of Clubs

By the early 1800s, the Curragh in Kildare became a hub for rook and magpie hawking. In 1857, Captain Henry Salvin and John Barr, falconer to Maharajah Dhuleep Singh, practiced magpie hawking here. Publications from the time mention hawking for woodcock in Monaghan and exciting rook hawking adventures at the Curragh.

In 1860, a meeting at 212 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin—chaired by Lord Talbot de Malahide—established the Irish Hawking Club, with a £50 donation from Dhuleep Singh.

Yeats, Modern Writers, and the Revival of Falconry

W.B. Yeats frequently used falconry imagery in his poetry. In The Second Coming (1920), he famously wrote:

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre / The falcon cannot hear the falconer…”

In the 1950s, Ronald Stevens moved to Connemara and became a pivotal figure in Irish falconry. His home, Fermoyle Lodge, became a centre for falconers. His books—Observations on Modern Falconry, The Taming of Genghis, and My Life with Birds—continue to inspire.

The 20th Century to Today

Under the revived Irish Hawking Club in 1967, led by figures like Rowland Eustace, falconry thrived once more. The sparrowhawk gained popularity in the 1980s and 90s, reflected in Liam O’Broin’s The Sparrowhawk: A Manual for Hawking (1992), which remains a classic.

Thanks to regulated wild harvesting and successful breeding programmes, access to birds of prey has never been better. Goshawks, once extinct in Ireland, have returned. Tiercels (male peregrines), sparrowhawks, and even the smallest falcon—the merlin—are all flown today.

A Living

Heritage

Falconry in Ireland demands time, skill, and commitment, which is why the community remains small but passionate. In July 2019, it was officially inscribed on Ireland’s National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In December 2021, it joined the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, alongside traditions from nearly 30 countries.

Today, falconry stands not only as a link to our past, but as a living, sustainable way to engage deeply with the natural world.

Splash

Splash